Blog

The Therapeutic Power of Outcomes Measurement in Mental Health Care

By Michael Boroff, Psy.D.

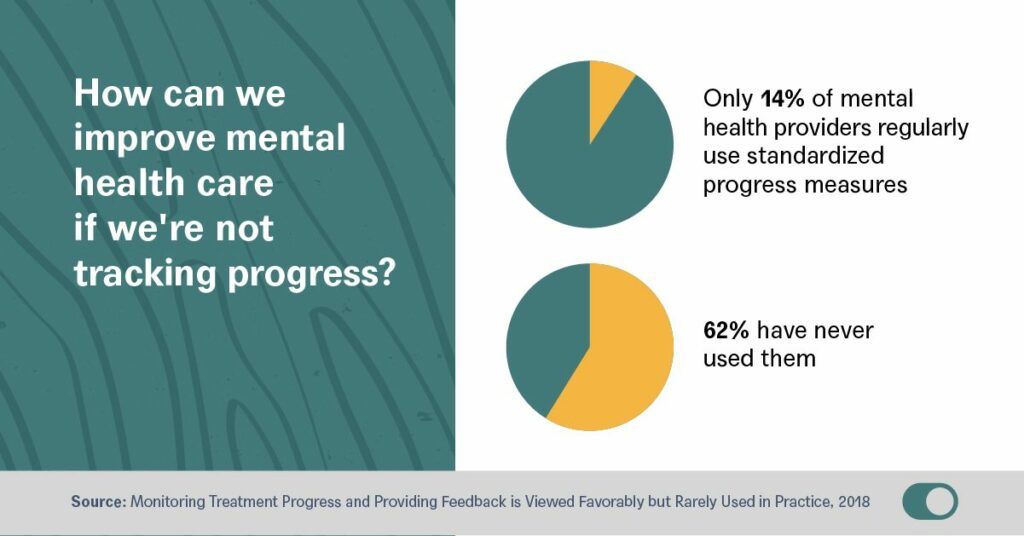

I became a clinical psychologist for one reason: to reduce human suffering. I realize that may sound cliche, but after 15 years of practice and two years overseeing Crossover’s mental health programs, it’s still the North Star that guides not only why I do this work, but how I believe it must be done. After all, to know you’ve reduced suffering you need to measure the before and after and understand what worked and why. As obvious and simplistic as that may be, it’s unfortunately still not the standard for how most mental health care is practiced. In fact, only 14% of mental health professionals report regularly using standardized progress measures while 62% have never used them.

I was first drawn to Crossover as much by the culture of accountability as the integrated, team-based care model that sets us apart. Putting data at the center of care keeps us honest and relentlessly focused on doing better for our members. Most importantly, as a newly published study of our model reveals, it also drives significantly better mental health outcomes than alternative approaches.

How do we achieve this? At the heart of our success is Crossover’s integrated team-based model that treats mental health holistically rather than in isolation. When we work with our patients to identify any physical factors that could be contributing to mental health, and vice versa, we can achieve far better outcomes. But, as this study shows, our commitment to measurement-based care is an equally powerful driver enabling us to see with certainty if we are in fact achieving the outcomes we believe we are. At Crossover, our commitment to measurement is inclusive of patient-reported data on everything from anxiety and depression to measures of subjective wellbeing. That data isn’t just valuable in tracking and evaluating the impact of our interventions; it also plays a central role in spurring honest discussions of goals and expectations between therapists and their patients.

As therapists, despite our best efforts, we often find ourselves flying blind, never quite knowing how a patient is feeling about our approach to care. They may or may not be fully on board with the treatment plan, or believe we understand them and their needs—a lack of alignment that left uncorrected, can undermine treatment. As our study confirms, by soliciting and informing care with continuous, real-time feedback, we can strengthen the bond between member and therapist and empower members to take charge of their own care, leading to significantly better outcomes.

To rise to the challenge of the current mental health crisis, we must begin by humbly asking—and measuring—what’s working and why. Only then can we learn and do better.

To download and read the full study, visit the Crossover website here.